“Early in 1961, when I was a youthful 22 years of age, I’d completed my three year apprenticeship and was happily contracted to continue in the employment of the Associated British Picture Corporation. As luck would have it, I heard that art director John Box, who was based over at Pinewood, was looking fora draughtsman to go out on location to Jordan for a film about the life of T.E. Lawrence which David Lean was directing...

…A young, good-looking chap started popping in the office to ask me about the props we were drawing up, from Bedouin tents to canvas buckets. I didn’t think too much about him, and just assumed from his daily enquiries that he was a prop man. After a few days he asked if he could catch a lift with me back to the hotel each evening. I was only too happy to oblige. This went on for a while, and I only ever knew him as ‘Peter’. Then one evening, he never arrived, so I waited well beyond my usual leaving time and when the driver asked what the problem was I said, ‘I’m waiting for Peter the prop guy’. Well, you may be one step ahead of me by now, but it turned out that Peter was not a prop man at

all – he was the star of the film, Peter O’Toole!”

“Cleopatra was certainly the most expensive and heavily publicised film ever to move into Pinewood. Sets of previously unheard of dimensions were constructed on the backlot. However, soon came the first of the many problems that dogged the production – a shortage of plasterers. The situation became so desperate that the studio finally resorted to advertising on prime-time TV to fill the vacancies.

The size of the production was giving cause for concern and, before a foot of film had been exposed, the cost had easily exceeded £1m, and there was still a sixteen week shoot to get under way. The imminent arrival of 5,000 extras was the next headache. Pinewood’s management laid on 28 extra tube trains from London to Uxbridge, and 30 buses to shuttle to and from the station non-stop. Mobile lavatories were hired from Epsom racecourse, and massive catering marquees were erected to house the mountain of food for meals. However, all the planning and organisation was wasted – along with all the food– when torrential rain forced shooting to be abandoned.

Then real disaster struck. Elizabeth Taylor became dangerously ill and had to undergo an emergency tracheotomy. Production was halted, and Joan Collins placed on standby as a replacement. Miss Taylor’s recuperation was a slow one, and what with the miserable

British weather raining down on the sets day after day, the decision was made to transfer production, and Ancient Egypt, to Italy – where the climate was more conducive to Miss Taylor’s health.”

“Dr No was thefirst of the long-running series and was set to star a relatively unknown actor named Sean Connery. If anyone had said then that they had an inkling of an idea just how popular the franchise would become, then I’d say they were lying; as far as we were all concerned it was just a relatively modest budget spy film.

On one occasion I was asked to ‘stand by’ with the second unit on the twisting mountain road that Bond is chased down by a hearse full of assassins. I had to build a camera hide down a slope from the road, for the hearse to crash towards. I realised that the weight of the vehicle, coming down a 45 degree slope, would need something more than I could build around the hide to stop it being demolished, should the car hit it. So with the help of a lot of railway sleepers, the construction gang built it on top of a gully running down. We were pretty confident that, if the hearse left the road at the correct spot, it would be trapped in the gulley to continue the driver-less journey down to the bottom of the mountain.”

“With the success of Cliff Richard’s third film, The Young Ones, it was inevitable that another film with a few more ambitious locations would be on the cards.

For one of the biggest scenes of the movie, Cliff was driving whilst singing the title song. Disaster struck when the gearbox under the steering column broke free. To keep the cameras turning, John Graysmark and myself crawled under the rostrum and held up

the metal support, enabling Cliff to complete what was needed. As you can imagine, every time I hear him sing ‘We’re all going on a summer holiday’ I think back to being under the bus holding it all together!”

“I suppose out of all the films I’ve worked on, taking the designer’s ideas and transforming them into working drawings, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey must rank as the number one in terms of challenges, workload and sheer vision.

Today, nearly five decades later, the film still holds up and, when you think that’s set against productions of recent years with the benefit of multi-million dollar digital imaging techniques, it really does say a lot about Stanley’s sharp eye for perfection.

Shooting in a giant wheel gave us many problems, and overcoming them with Stanley’s continual ‘input’ was always a challenge, but love him or loathe him, you always put in your best work.”

“The budget was said to be around $26 million which, at that time, was a massive amount, but our canny producer Joseph E. Levine – on the back of the all-star cast, including Sean Connery, Laurence Olivier, Michael Caine, Gene Hackman and Anthony Hopkins, to name but a few – had pre-sold the distribution rights around the world and was in profit before the cameras started turning!”

“Many locations for the ice planet ‘Hoth’ were considered.The script called for a treeless area of snow, ice and mountains, though of course it had to be accessible for the crew of about seventy people and all the equipment and generators needed. It became a really tough call. That is, until Finse (an area in the Ulvik municipality of Hordaland, Norway) was suggested.

...With the weather dictating our outdoor shooting it was decided to bring Harrison Ford out a week early. We all thought the snowploughs would clear the railway tracks, but an area coming up from Oslo had a large snow-collapse onto the tracks, meaning the ploughs couldn’t operate and it all had to be cleared by hand. Harrison was already en route by the time we received the news, but he could only get within 30 miles of us. As we’d planned to film scenes with him the next morning, a rescue plan was set in motion.

Our location manager took a bottle of vodka to the driver of the snowplough engine and bribed him to go down the line as far as he could to pick up our leading actor, who’d agreed to walk part of the way. I was told that they all returned, very merry, about midnight.”

“Whilst in Dallas, I was asked to visit Lee Harvey Oswald’s rooming house at 1026 North Beckley, as we were planning to reconstruct part of the house for the film. The owner, Mrs Roberts, showed us his old room and surprised us by saying that she had kept all the original bedroom furniture from 1963, and it was all stored in her garage. On a similar note, the lunch room that Lee Harvey Oswald was found in after the shooting, was on the second floor of the Texas School Depository Building.

He was found, by Officer Marrion Baker, sitting eating his lunch. Since we planned to recreate this room from police photos taken at the time as part of a‘crime scene’, I was excited to find that all the original cabinets, in the original pink colour, were still in storage in the basement. Having pulled them out, we were able to integrate them into our film set.”

“On the final day of the recce we drove out to the Statesville correctional facility itself. This was where we were going to film a prison riot using dummy rubber weapons. We met the governor, and he said they would shortlist some inmates we could use as extras during the ten days’ shooting within the prison.

We had heard from the governor that, on a previous film shot in the prison, one of the prisoners had chatted up a third assistant female director and, wearing her crew jacket and her earphone and microphone set, calmly walked out and boarded the crew bus at the end of the day… you can imagine the security for us going in and coming out each day whilst we were shooting.”

“Each kennel floor was covered in a thick carpet and adorned with toys, and divided into pink and blue sections to keep the puppies happy. Such was their luxury that we were sure it wouldn’t be long before TVs and video machines would be installed to entertain them when they were not required on set.

The love and affection shown to these puppies by twelve attractive kennel maids was top-notch; even some of the crew began to envy them. On one occasion on the huge H-stage, a lamp was put under some tinder dry fir trees to create an effect and suddenly they ignited and burst into flames. The fire spread from the bottom to the top of the trees in seconds. The call went out ‘THE PUPPIES, THE PUPPIES!’, and as the trainers rushed around picking up the pups from the set, one electrician rushed by me saying, ‘Sod the puppies, what about the humans?’ Luckily the standby firemen were very quick on the ball and put out the burning trees.”

“Saving Private Ryan is an American epic war film set during the invasion of Normandy in the Second World War, starring Tom Hanks and Matt Damon, and directed by Steven Spielberg. My main job on this movie was to source all the vehicles, tanks, planes and boats required.

Throughout the preparation period of the film, we only had one conference call to Spielberg, as he was busy in LA cutting his last film. He had a great trust in us all to deliver the main D-Day Landings beach set, which we finally did after much hunting for a location in Ireland.”

“Although there had been a ‘reboot’ of Batman for the big screen in 1989 (with Tim Burton at the helm), and into the early 1990s, with everyone from Michael Keaton to George Clooney donning the cape, I was intrigued to hear that British director, Christopher Nolan, was going to breathe new life into the franchise in 2005. I was even more intrigued when I was asked to join the new film, to take on the complex ideas that the director and his American production designer, Nathan Crowley, had come up with for the new Batmobile.

Naturally, security on a film such as this, which has a huge amount of hype and expectation attached, is always tight. So much so, I was asked to hide the model and cover my drawing board with a dust sheet every night in case the cleaners saw it.

The first prototype went out to a vehicle proving ground under much security, and stunt driver George Cottle was the lucky guy to put it through its paces. To his delight, and ours, it could do everything that was asked of it. This was still two weeks before the start of filming, so for once we were ahead of the game. At this point a second Batmobile was started – you always need a spare on a movie like this. To see the ‘Tumbler’ (the scripted name for the Batmobile) going into a sideways spin on the test track was proof enough that the special effects engineers had fulfilled Christopher’s objective, that it would ‘perform like a two and a half ton sports car’.”

“The whole set was to be constructed on the 007 Stage at Pinewood, and built into a vast hydraulic metal rig that would move the set down into a tank of water. The whole rig weighed in at 80 tons, and it was the largest ever built for a film. It was all controlled from a bank of computers and a massive keyboard.

The film went on to become the highest grossing Bond film, only to be beaten by Skyfall in November 2012.”

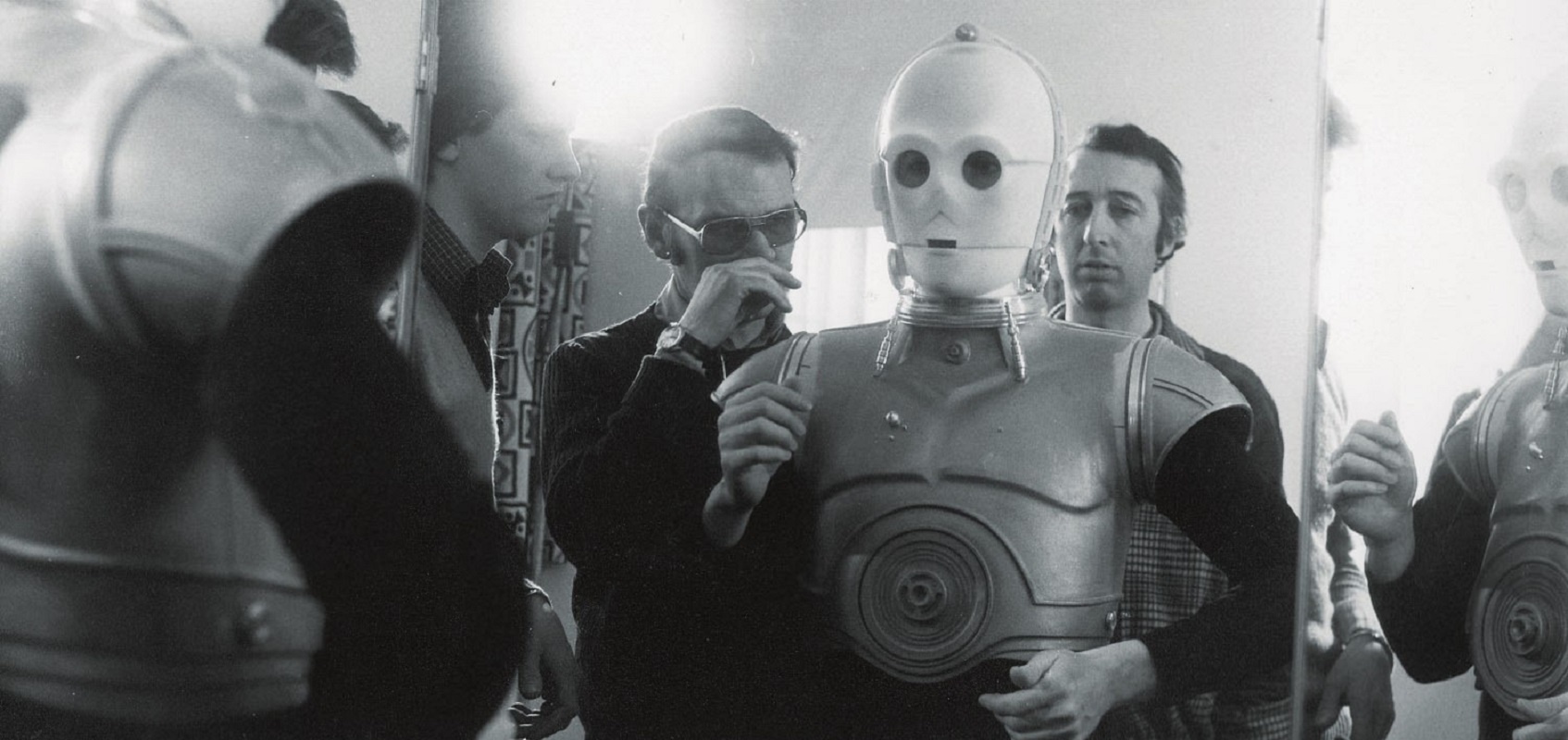

Tomkins fits Anthony Daniels into his C-3P0 suit

Tomkins fits Anthony Daniels into his C-3P0 suit

Glenn Close as the iconic Cruella De Vil

Glenn Close as the iconic Cruella De Vil

Bond's Aston Martin completed seven full rolls, earning the stunt a place in the Guinness Book of Records

Bond's Aston Martin completed seven full rolls, earning the stunt a place in the Guinness Book of Records