By David Charter & Bruno Waterfield

Prime Minister David Cameron

Prime Minister David Cameron

Cameron's wish list

David Cameron’s objective at the European Council is to move his renegotiation out of the initial ‘launch’ phase and onto the next stage without giving any more detail on what he wants. Mr Cameron will in effect repeat in front of all EU leaders the broad outline of his demands he has given in private one-to-one meetings in the weeks leading up to Thursday’s meeting.

This sketch, deliberately broad-brush, divides Britain’s demands into four ‘buckets’. They are:

1. Restriction on migrant benefits entitlements Arguably the most difficult to achieve and the area on which Mr Cameron has been most explicit. He wants to deny migrants’ access to benefits until they have been working for at least four years and to deny child benefit payments to offspring not living in the UK. It will require treaty change and is opposed by a number of EU states particularly in eastern and southern Europe. Mr Cameron has also previously suggested he wants new ‘transitional controls’ that would stop newly-joined members of the EU from being able access the UK labour market until they had reached a set level of economic development.

2. An exemption for the UK from the legal premise enshrined in EU law that there should be ‘ever closer union’ between member states Although largely symbolic this will also require treaty change, senior government figures believe, adding to the complexity and difficulty of winning cross-EU assent

3. Protecting the interests of non-euro countries as eurozone countries deepen political and economic ties Even if Mr Cameron hadn’t promised a referendum he would need to ensure that Britain isn’t disadvantaged after the next round of eurozone reform. Some change to voting rights will be needed to ensure that ‘ins’ can cooperate in a way that doesn’t hurt ‘outs’. It’s going to be messy and complicated. It’s in this ‘bucket’ that Mr Cameron also places a vague formulation about giving national parliaments a ‘red card’ over Brussels law – a sop to the Eurosceptic demand for full parliamentary veto that satisfies no-one.

4. Completing the single market and cutting red-tape By some distance the least contentious area. The European Commission is already committed to reducing regulation and making the EU a more business-friendly. Nevertheless Mr Cameron will present any changes as evidence of the success of his renegotiation and will be keen that Brussels plays along.

Key dates

2015 --------------------

June 25 & 26 summit David Cameron will unveil his “renegotiation” plan and the steps to achieve it in a short presentation to other EU leaders at the end of a working dinner season of the European Council, an agenda item billed by officials as “and finally”. There will not be a major roundtable on the prime minister’s “outline” and Donald Tusk, the former Polish leader who chairs the meetings, will be charged with coming up with a package over the coming six months. Summits are unpredictable and, warn some diplomats, François Hollande could register some of his objections at Mr Cameron’s desire to choose Europe “à la carte”. Others will press him on the date of his planned referendum.

Summer & autumn Mr Tusk will work closely with Sir Ivan Rogers, the British permanent representative to the EU, Tom Scholar, Downing Street’s “sherpa” and Ed Llewellyn, Mr Cameron’s chief of staff on the detail of the renegotiation, especially treaty change.

One important focus will be for George Osborne, the chancellor, in winning support for British “safeguards” to protect the City of London and single market from an increasingly centralised eurozone voting bloc.

Jean-Claude Juncker, the European Commission’s president will also play a role on areas where EU legislation could be overhauled or changed. He will make proposals on EU free movement, with reforms expected in 2016.

October 15 &16 summit The prime minister and Mr Tusk will update the summit on progress and, if necessary, will seek guidance from EU leaders if any problems have come up - the French president could be trouble.

By this stage, Mr Cameron will be under pressure from Conservatives to spell out what he wants ahead of a true “crunch” summit in two months time.

December 17 & 18 This summit is Mr Cameron’s renegotiation rendez-vous with history, the moment he will spell out the detail, in terms of treaty change and legal reforms of his demands to other EU leaders. It will be the moment that some will push back.

During talks that will go through the night, the Conservative leader will have to show the British public that he fought and won on demands for his renegotiation to be taken seriously.

The European Council meeting will open one full-on negotiations, expected to include treaty change, with a deadline for conclusion, probably to be set for October 2016 - December at latest.

France and Germany are insistent that negotiaitions do not continue during elections in both their countries during 2017.

Other European leaders will want to stick to a “simplified revision” of the treaties and any more major reforms might be delayed until 2019, when more radical treaty change is planned to create a eurozone treasury.

2016 --------------------

January - Dutch EU president In the new Year, Mark Rutte, the Dutch prime minister takes over the, largely symbolic, six month rotating EU presidency. As Mr Cameron’s closest ally he will use the time to promote reforms and cuts to EU red tape.

Frans Timmermans, the Dutch commission vice-president who is second in command to Mr Juncker, will also roll out lots of helpful “better regulation” to show how business and consumer friendly the EU is.

March - EU summit on competition EU leaders will strain every sinew to highlight reforms to the EU’s single market and how it benefits Britain. Mr Cameron’s renegotiation will be at its height.

June - EU summit Depending on when Mr Cameron has decided to hold the referendum this could the moment when EU leaders - by a unanimous decision, with 28 vetoes around the table - decide to amend the treaties in a “tidying up exercise” for the eurozone.

The prime minister could hitch a ride for the UK on the revision but cannot use it to get through any reforms that change the balance of powers in the EU.

October - summit Many EU officials and diplomats are hopeful that the Conservative leader will be in Brussels fresh from a referendum victory. Other possibilities are that the summit could be a venue used to roll out fresh “victories" after a staged battle for Mr Cameron at the height of the referendum campaign.

December - summit This is the cut-off most expect for the negotiations because of French concerns that the British debate could spill over into the country’s presidential elections in spring of 2017. President Hollande is fighting off left-wing critics of eurozone austerity and Marine Le Pen’s Front National, her flagship demand will be a referendum. Mr Hollande has made it clear he does not want negotiations remaining open during the campaign, the socialist leader also fears that Nicolas Sarkozy, if he is the conservative challenger, could use the ongoing talks to demand a French renegotiation modelled on Mr Cameron’s.

2017 --------------------

January to May France will be gripped by presidential elections. If Mr Cameron is planning a vote in 2017 he will avoid this period, the French president has asked him to.

July Britain holds the EU rotating presidency and it could be the perfect time to go for a referendum, showcasing Mr Cameron’s hand on the helm (even if symbolic) of a reformed EU. Referendum legislation meaning that “purdah” rules will not apply will provide plenty of opportunities for the government to announce bold British reforms during a campaign.

Angela Merkel, the German Chancellor, faces elections on 22 October meaning a referendum could be held late that month.

December - EU summit By December 2017, EU leaders will know if “Brexit” is on the cards or not. This will be a crisis summit if Britain has voted against EU membership.

Ironically, the end of 2017 and the beginning of 2018 will be the beginning of an EU debate about major treaty change to bring “fiscal union” to the eurozone. This could be the opportunity for a “protocol”, including elements of Mr Cameron’s demands, to enter a new EU treaty by 2025.

FRIEND OR FOE?

Tap on plus sign for more information

WHAT'S AT STAKE

Britain's share of trade in goods with the EU

Britain's share of trade in goods with the EU

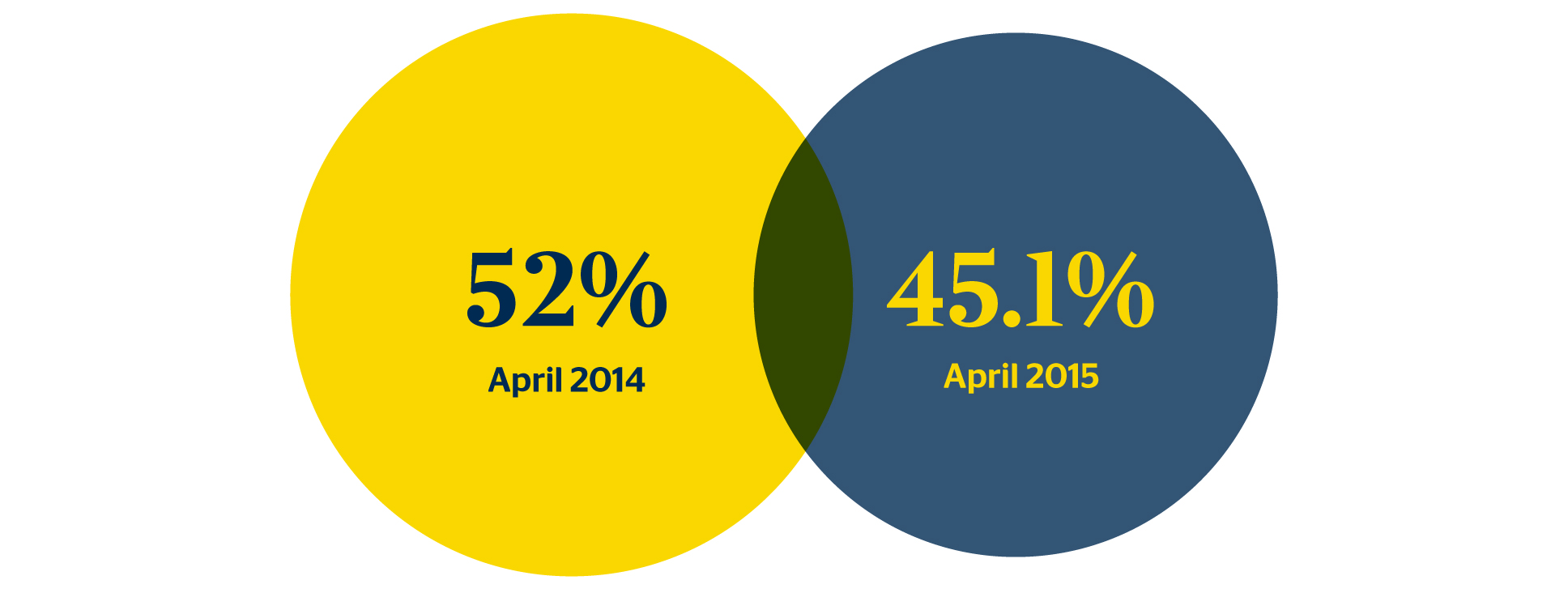

The EU is by far Britain’s largest trading partner. Share of trade in goods with the EU was 45.1 per cent in April this year, down from 52 per cent the previous year.

Trade with the EU nations is 55 per cent higher because of the Single Market than would be expected by their size, according to the Centre for European Reform.

The top 100 EU directives cost the £33.3 billion a year, according to Open Europe, including £4.2 billion a year for the working time directive and £2.1 billion for the temporary agency workers directive.

The working time directive guarantees four weeks paid annual leave a year for workers and limits the working week to 48 hours, with the possibility of individual opt outs. The temporary agency workers directive guarantees equal treatment for agency staff as permanent employees.

Britain's net contribution to EU

Britain's net contribution to EU

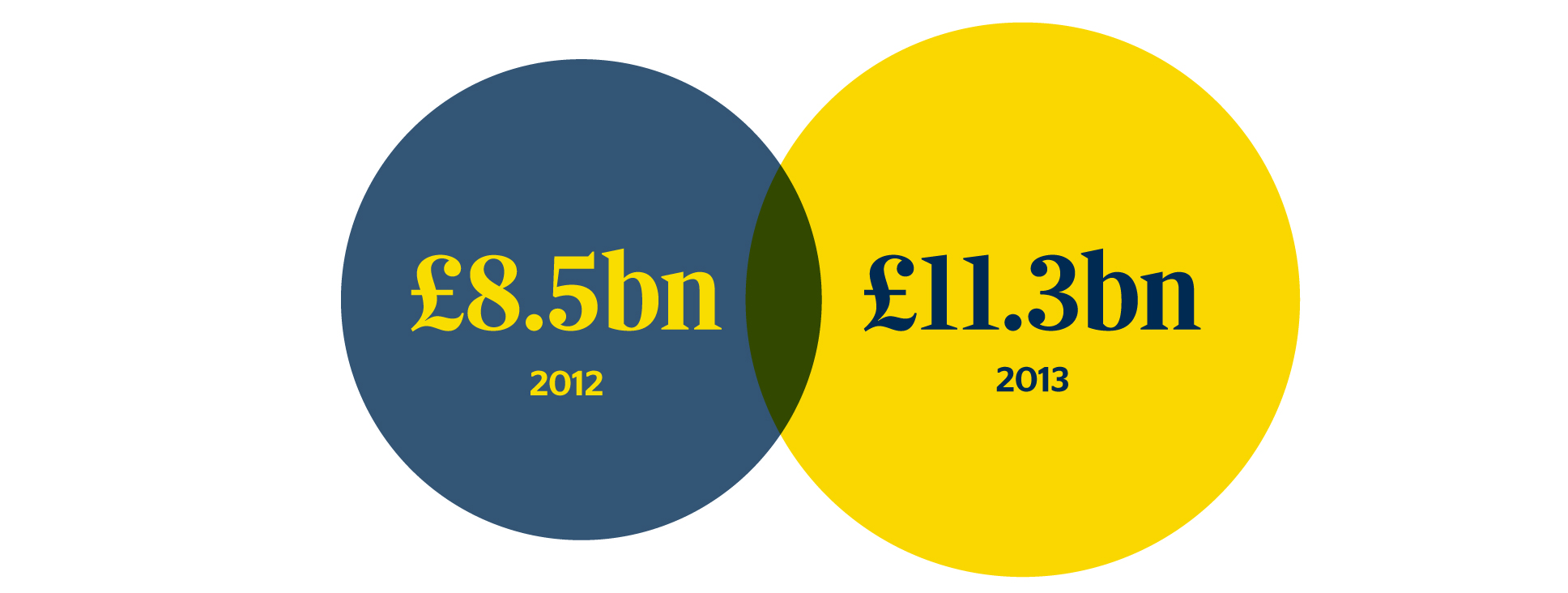

Britain made a net contribution to the EU of £11.3 billion in 2013, up from £8.5 billion in 2012, according to the Office for National Statistics.

Non-EU members Norway and Switzerland make contribution to the EU for taking part in the Single Market. The equivalent annual gross contribution for Single Market access after Brexit has been estimated at between £2 billion to £3 billion.

2007-2013 UK contribution and how much we got back

2007-2013 UK contribution and how much we got back

Over the 2007-2013 EU budget, the UK contributed £29.5 billion to EU regional funds, and got back £8.7 billion, making it the third largest net loser from the funds after France and Germany.

Scotland will receive £3.4 billion and Wales £2.3 billion in EU regional funding from 2014-2020. Over 30 years after it joined in 1981, Greece received euros 61.7 billion in EU regional funds.

Around 2.3 million EU citizens live in the UK while around 2.2 million Brits live in the EU, according to a parliamentary answer last year.

Around 65,000 EU nationals receive jobseekers allowance in the UK. At least 30,000 British nationals receive unemployment benefit in EU countries.

The Common Agricultural Policy took up 39 per cent of EU funding in 2013. Nearly 200,000 British farmers received £3.3 billion a year from the EU, while £5.4 billion went to EU farming from the UK in 2013, a net subsidy to European competitors of £2.2 billion.